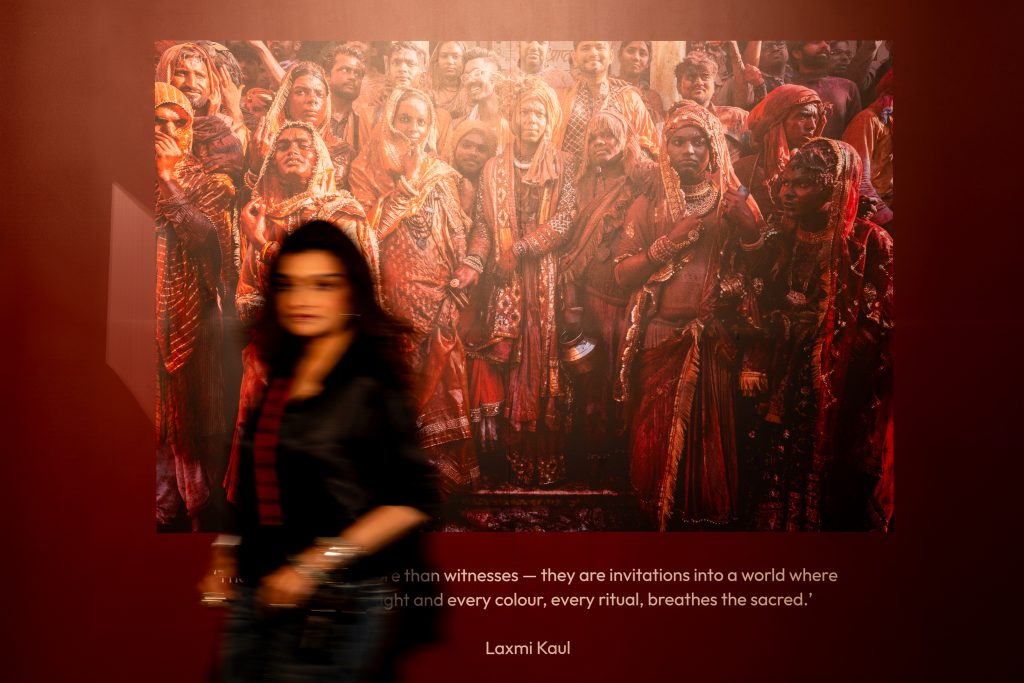

Leica Singapore presents one of the most captivating photo exhibitions ever, featuring three major festivals in India, photographed by Laxmi using Leica cameras. The pictures speak for themselves; they are colourful, they evoke emotions, and more than anything, they are thought-provoking, making you wonder how these photos were achieved and the blood and bruises that went into creating them.

We had the privilege to speak with the photographer Laxmi, about her pictures, and the meaning behind them.

NYLON: What is this exhibition about?

LAXMI: It is my love story with India and the festivals that are so beautifully portrayed in India, but they don’t get a chance to be seen by people outside of India.

The photos in this exhibition are basically an amalgamation of three very major festivals that are held; one being the Kumbha Mela, which comes once every 12 years. Then there’s Holi — a festival of colours, which happens every year. And Theyyam is another festival down south. The other two are up north in India.

Each festival is very different in its own way. But the one anchoring point for all the festivals is basically faith. And faith, to me, is a very deep subject. Everybody has their own faith, and everybody likes to follow their own faith in their own way. Faith manifests in different ways, so these are just manifestations of faith in different ways; one with colour and dance, one with taking a dip in the holy rivers and believing that you will get purified and you will be closer to salvation in the journey of your spiritual life…

N: What made you want to photograph all these festivals?

L: I didn’t go to seek something big; I never I go into shoots very innocently. I don’t plan, I don’t have an agenda. I don’t say, okay, these are the five shots I’m going to get from this shoot. I will just go in instinctively, feeling that this will be a story that I would like to know more for myself than for anybody else. But what happens in turn, is that I realise that this is larger than life, and this is the reason why I wanted to exhibit these pictures. What I thought was something that I was doing for myself, I realised very quickly that this is much larger than that.

There’s no withholding here. I needed to show it, because Indian culture is so vast and so so deep; deep rooted in science as well as spirituality. And it needs to come out, it needs to be shown. And it has so many facets and so many aspects that just somebody hearing about it versus somebody seeing it and then feeling it, that is what I wanted.

I wanted to bring out the stories behind the larger story, which is what this exhibition is about. They are the stolen moments, the stolen glances of the smaller story that actually makes the bigger story.

If there is no faith in people, there will be no festival. If there is no undying devotion to Lord Krishna, there will be no Holi; if there is no faith that the goddess or the God that I love so much is going to now unite and be one, then there will be no Theyyam. So that belief in 2025 is still important; it’s very relevant.

And if you’re not going to hold on to our past, what are we going to show our kids and what are we leaving for them? We’re leaving only technology and social media, and that’s about it. What about our roots? What about our culture, whether it’s Indian, Chinese, Thai, be it anywhere in the world; even Christian or Muslim — what are we leaving for them? I want to leave something. I want to leave a footprint behind for people to know that, okay, maybe 50 years down the line, there’s no more Holi celebrated; but look, these are the pictures. This is how it used to be. This is my documentation. This is my love. This is the oxygen that flows through my veins.

N: How long did it take you to shoot all the photos in this exhibition?

L: This exhibition was shot over a decade. I shot in 2009, 2013, 2018 and 2020.

N: What were some of the challenges that you faced while shooting these pictures?

All three of these stories are shot in areas that are male centric. Up north, there’s a very strong male dominance. Down south is the same. In fact, anywhere in India is the same. And if you’re a female photographer in a man’s arena, it’s not easy to be accepted there. People will think, “How dare she? She thinks she has the strength to be here and deal with all this and shoot us.” That’s the invisible feeling or energy that I always feel.

For example, during Holi, it was completely male dominated. I walked into this place and there were only men all around me, and I was like, what, just what is this? How am I going to deal with this? Because not everybody is educated and not everybody’s cultured. This is not Singapore where somebody will say, “Excuse me. Can I pass through or can I stand in line, or whatever?”

For Holi, it’s a man’s world. I would be identified as the one female there. And, people would think, “Oh, she also has a camera, so let’s aim at her. Let’s throw colour. Let’s trouble her. Let’s weaken her.” And initially, I did get weak, and I did get overwhelmed, and I found a corner and I went and sat down, and actually cried. I was wailing and crying because I was fed up of being groped. I was fed up of being touched.

I’ve been living in Singapore for 27 years; I’m not used to living in India anymore. I’ve lived more in Singapore than I have lived in India. I left India at 18 so I am also Singaporean in a lot of ways. And imagine a man [in Singapore] coming in and doing that; he will be in court the next day. Police complaints will be filed here.

[In Holi], it is like it’s acceptable because of the game of Holi; the play of Holi, it’s all full of fun. It’s a fun festival, so whatever you do is acceptable. So imagine they’re throwing colour on you, and then you’re wiping your eyes, because you need your eyesight. And then they’re like, let’s throw colour on her camera. What can I do if my camera gets spoiled? But luckily, the Leica doesn’t get spoiled, right? It’s all weatherproof, and I was the only photographer there that didn’t have anything covered.

A lot of the other photographers would cover their cameras with cling wrap and safeguard it, and put it between those rain guards and all of that. I was the only one [without the camera covered], and they were looking at me like… you mad woman. I was like, no… I’m not the mad woman. I feel bad for you, because luckily, I have the fortune of using the world’s best cameras.

But having said that, it was not like I was in the line of fire at all times. I did feel weak for some time, especially on my first trip, because I didn’t know what to expect. We play Holi in our cities all over India, throughout the year; throughout my life I’ve played it, but it’s never been like this, to this kind of scale. So I gathered myself up and I said, I’m here now. I have to make the most of it. I have to fight this. If I’m going to leave this and go away, what am I going to tell the other female photographers? What am I going to show? What am I going to tell my children? That mom just left because it was difficult for her? That was running through my head. And more than that, I was keen on shooting people who were so devoted to this and so harmless. And those are the people I wanted to shoot, and those are the people I wanted to showcase. And if I gave up, I would not have this today.

I’m also not very tall, so it’s very easy for me to just somehow get lost in a big crowd. People are doing what they want; they’re taking their dips in-between huge crowds. I have to find my moments in that and take images which are compelling, which have meaning, have some kind of story behind them. It’s very difficult when you’re in very large crowds, so much so that you don’t have space to even lift your hand up to put the camera to your eye.

I think the common factor that binds all these three festivals is the sheer roughness of it and the sheer idea that [people think] you can’t do it. You’re a female photographer, why are you here? I will be here. I will be here tomorrow. I will be here the day after, and I will be here again next year.

N: What gear did you use to create these photos?

L: For Holi, I used the Leica SL a lot because it’s all weatherproof. I also used the Leica M10. I was wearing a raincoat, and I would open the zip and quickly take the M10 out and take a picture and put it back in, just to conceal it.

Mainly because I love portraiture so much, I tend to gravitate towards the 50mm lens. I have a very strong feeling towards portraiture, because I like the human connection. It’s very important that I connect with people or my subjects before I make an image.

But because it’s Holi and it’s such a large scape, I did shoot with the 28mm lens a lot. [Compared to the M], the SL, of course, is a bit more lenient. I had the 24-70 lens so it gave me a little bit more breathing space so I could be a little further away from the line of fire, and the men getting upset about a woman being there. I could move away and zoom in and use the 70 and shoot.

Laxmi Kaul’s Photo Exhibition, Utsav – India in Celebration runs from 16 May to 30 July 2025 at Leica South Beach Quarter (located at 36 Beach Rd, #01-01 South Beach Quarter, Singapore 189766).