By Adele Chan

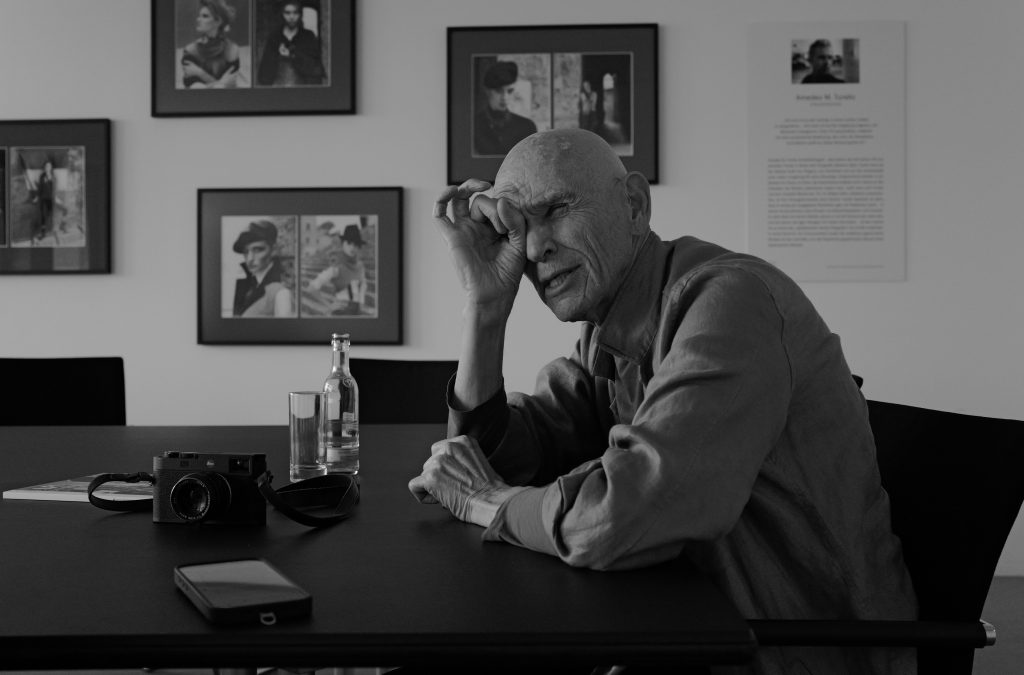

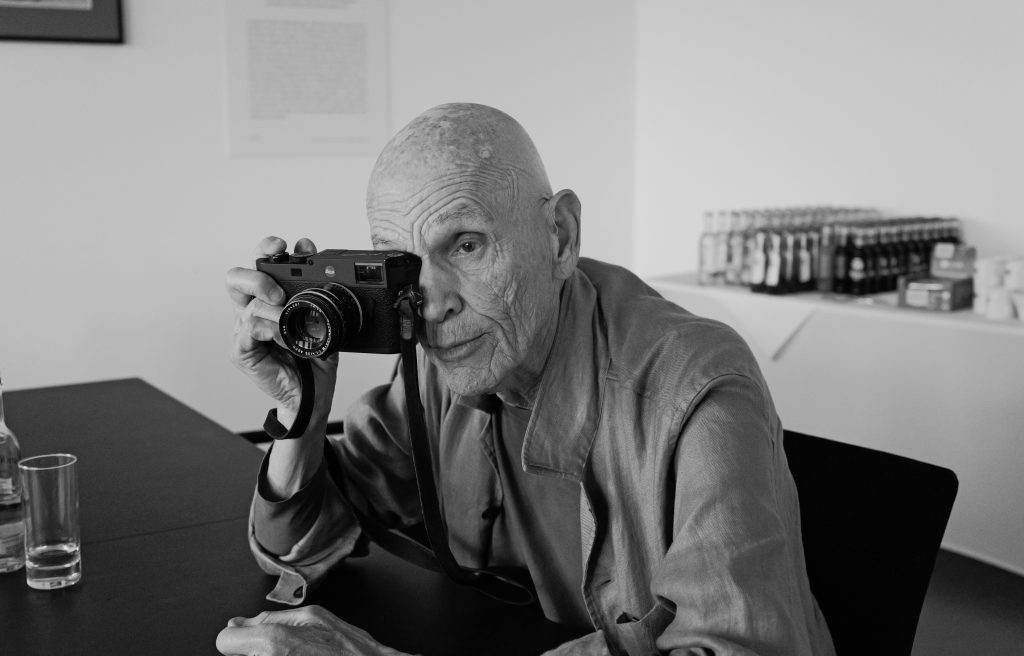

Joel Meyerowitz is a legendary photographer whose work was instrumental in changing the photography industry’s attitude toward using colour photographs and having them being accepted as serious art. His incredible portfolio spans across decades, and as Leica celebrates its 100th anniversary, I was given the opportunity to speak to Joel about his lifespan of work, ethics in photography, and pretty much everything his fans and audience would want to know about him.

NYLON: What inspired you to pursue a career in photography?

JOEL: I didn’t know I was going to pursue a career in photography. I was a painter, and I was studying art history, and I was working as an art director, graphic designer, and suddenly, watching Robert Frank’s work. I had a flash understanding about the camera, and I knew nothing about photography. I didn’t even own a camera. I suddenly saw, by the way he was working, he was shooting a little booklet for me that the camera stopped time. And I never really understood that or thought about it. And when I was walking the streets of Manhattan, every day, I would see things on the street, and they moved me, or they touched me in some way, and I would try to integrate them with little sketches and integrate them into paintings.

But suddenly, photography seemed to be a new answer to a question I hadn’t even posed myself. And so when I went back to the agency after this shoot that he did, I told my art director I was quitting, and I wanted to be a photographer. And it was the first time I ever said that, you know, and he was incredibly supportive. The art director just said, “here, borrow my camera and make some pictures”. And I went out on the street, and I felt like I was free in a way that I hadn’t anticipated. So that was it. I had no goal. Early on, photography was totally beyond my interest range.

N: What’s a memorable experience or any project that has had a significant impact on your work?

J: Well before there were projects, there was just work. You know? I mean, nowadays, people are so educated about photography, their teachers get them to think about projects. For me, all I wanted was to be out on the street and not in an office. And I just wanted to walk the streets watching human behaviour, all of it — the high and the low, the tragic and the comic, the compassionate and anger… I mean, all of our human emotions. And I began to realise within the first six months or so that there was more to photography than putting something in the middle of the frame. For me, if something was interesting over there and something was interesting over here, to me, just movement or colour or gesture, I tried to put the frame around them so that I could put two dissimilar things in frame to make a new meaning.

And that became my search. It wasn’t a project; it was, how do you work on the street? How do you become invisible so that nobody gets it that you’re making a picture of them. How fast can you respond to the things that stimulate you, so organising and understanding the physicality of working in an environment that you cannot control seemed to me to be an art form — like ballet or like a sport. So that’s where I began.

You know, only later on, by looking at my work that I accumulated, did I conceive, oh, if you put all these pictures together, you have a shape, you have a subject. So the subject became the concept, in a way, but the concept didn’t come first.

N: As a street photographer, have you experienced a situation where you take someone’s photo and they notice it and they’re not happy?

J: I’m out there, and I’m present all the time, and I can work as close as I am to you, and people don’t see me. So I learned how to do that young, and I’ve never had anyone angry with me. First of all, if you work quickly enough, particularly before digital, people didn’t think you were making a picture of them. If I took a picture of somebody as they were walking at me and they saw me raise the camera, they often would look behind them to see what was so interesting back there that that guy was taking a picture, they couldn’t imagine that I was photographing them.

So speed and decisiveness and a sense of moving in a way that you could fake it out, fake people out. And also, I have to say, when you’re young, there’s a certain kind of charm that you develop so that you can get whatever you want on the street. And I had that as a native New Yorker; I knew how to do that, and so I never had a No, and I didn’t ever threaten anybody with a camera like some photographers we know today who shove it in people’s faces and basically are kind of brutal, you know, even brutal starts to bear their name. Anyway, for me, it was the joy of being with other human beings.

N: Are you a technical photographer? Do you work in full manual control and shoot from the hip?

J: Oh, no — the Leica is great. From here at two feet to here at infinity it’s nothing. If you had a single lens reflex camera and you were doing this, it would take forever to get the focus. So I know where the focus is all the time. And I look; I actually look through the camera to make the photograph. And I set everything manually. And it was always that way with Kodachrome. Kodachrome had an ASA of 25 you couldn’t fuck up, you know, you had to be so precise with your photograph, with your exposure, so it would be like 250 of that 4.5 or 250 of that 5.6, so that everything was beautifully exposed.

And I’ve made photographs from a moving car. I had a show at the Museum of Modern Art of all pictures made from the seat of a moving car, as the first conceptual photography show; interesting that was in the 60s, but on the street, you know, in a car, you’re going 100 kilometres an hour. From the car, I used to be shooting at a 1,000th of a second.

On the street, it’s always 250 [shutter speed]. It’s not so super fast that your exposure is kind of compromised at the high and low ends. It’s a good mid range exposure, and it gives you beautiful colour when you’re using colour film. It also renders beautifully digitally. So I stayed with that as my go-to exposure.

But I feel that photography is not always guesswork; it has to be something you are really committed to, that you believe in. My identity is wrapped up in my photographs. It tells me who I am. I’ve learned about who I am through the photographs I’ve made.

N: What advice would you give to photographers just starting out?

Trust your instinct. First thought, best thought. I mean, it’s basic kind of Zen thinking, in a way. But you know, if you pick your something that makes you go like that — even if it’s tiny, it means you, your entire being, you have been surprised by something, something astonished you for a split second. It’s in that moment of astonishment that the camera comes up and you make a photograph. If you resist that, then you’re going to go against your basic instinct. This is training for basic instinct. It’s like a sport. It’s like a baseball player, a football player, a basketball player, a boxer, a skier or a tennis player. If you wait too long, it goes away and you miss the ball, then you’re no good, and you want to be in the moment, because photography is about a moment, right?

You press the button at 250th of a second, that’s 250th in that 250th of a second, there are 250 slices, and you’re choosing one. So it’s your identity. And if you learn to trust your instinct, you will learn who you are. You will learn your identity. What else besides learning and making art out of your own life is there? I mean in photographic terms, that’s true, and there are lots of people who work in the studio, and they do wonderful things in the studios such as still life and landscapes and all kinds of things.

Nonetheless, there’s always instinct at work. So trusting your instincts, listening to the Gasp reflex — I call it the Gasp reflex. When I go it’s me, because, look, we’re in a surround that goes 360 degrees in every arc, and something stimulates you, you have to know where that is, or learn how to find it. And then your work becomes about you, not about it, but about you. So you have to decide somewhere along the line you want to stay cold and just photograph things, or do you want to photograph your reaction to things?

It’s how I’ve lived since I began. I learned it in the first few months. I thought, oh, this is all about timing. And what is timing about? It’s about feeling. And where does the feeling come from? It comes from seeing. And what makes you see, initially, some kind of attention, gathering energy that you have. So step by step, it keeps getting to the camera, you know, but it has to pass through you to get there. And the you is the knowing you; not just the physical you — you who understand, there I am again on the arc of things. That’s me always over there, you know. So I think it’s a real education, and we all want to learn about ourselves, right?

N: How do you stay inspired?

The world is so much richer than anything that any of us can conceive of. You know, artists just scratch the surface of their potential and of what the world offers, and yet they make interesting work, right? You see land art, or you see paintings, or you see, you know, sculptures or whatever, people manage to focus their energies into something so staying inspired is just being in the world and having a sense of wonder that, oh, again, something so beautiful or so meaningful or so potent happens, and it’s as if it’s a never ending supply.

And you know, I’ve been doing this for 65 years now almost, and I’m still in awe of everyday reality. When I go out on the streets or wherever I am, it’s like, oh my God. How did that happen? Or look at the quality of the day, or the atmosphere. And so I think just being in touch with the joy of being alive and seeing is enough to keep you young really, because you feel the newness of the wonder of things.

N: Let’s talk about equipment. What is your everyday camera?

J: It’s the M11 with a 35 Summilux almost exclusively. And the reason for that, is if you were to look

straight ahead, you would see, without looking, you will feel your fingers moving. So we actually see at about 160 degrees. We have to really turn our head. But if we were to look straight ahead, our vision really is here, and this lens matches our vision. Our vision is around 75 millimetres, and a 35 millimetre is about 70. So this is a one-to-one lens; which means, if I pick up the camera now and I look at you, you are the size you are in the picture. You’re not too close, you’re not too far away. And so I want to relate to the world in a one-to-one way, and this objective and this body are what I carry with me every single day.

N: How did you find the transition from film photography to digital?

Well, I started shooting digitally in 1999 when the Japanese company, Olympus developed a little digital camera, and they flew the technician from Tokyo to Cape Cod to see if I could use their camera. It made a 1.8 megabyte file to see if I could use their camera to make very subtle pictures like my eight-by-10 view camera. Could you imagine?

And so I worked with it for a few days. They literally had to have the guy there in case something went wrong. They could fix the sensor or something. And I made some little prints right away. They were beautiful. Even though they were only eight by 10 inches, they were beautiful. And I thought, oh, yeah, this is going to get better and better, typical of computers, right? It doubles every year or every six months, or whatever it is. And I knew that, if it could be that beautiful, you know, in a really crappy, little, handmade camera, then it’s going to get better. Within 10 years, we’re going to have real amazing cameras.

And sure enough, by 2008 I had the first M camera, which did have some problems in the sensor, but nonetheless, it made some really beautiful pictures. I had the first one, and then it’s just gotten better and better, and some time ago, about 2010 or 11, I got an S, and I made a 48 by 60 inch print. It was for an exhibition, and so I cut the two and I put them together, and I analysed them with a loop, for grain structure, for pixels, colour rendition — for all of that. And when I went back and forth, there was no difference between the two. And that was from the Leica S, when I thought, well, if this camera, a new camera, is doing that now, why do I have to go in the dark room anymore? Why do I need to use wet when I could use digital? And so that was it for me, because if you spend 45 years in the dark room, it’s enough. I mean, do I want to spend my time in the dark, or do I want to be out in the world? Do I want to look at a screen and monitor and balance things there quickly and then print it right away and see it? Or do I want to go in there and slosh through chemistry? It was a clear decision.

N: What’s your post editing process like?

Well, you know, if you make a really perfect exposure as often as possible, and you just adjust for the neutrality of it all to make it look like the box, you’re in good shape. I don’t do any tricks. I don’t change the colour. No filters. I don’t remove anything. I don’t change the drop out and I don’t do any tricks.

And I was the first one to use Photoshop. In 1991, there was a beta site for Photoshop, so I’ve been there from the beginning. Wow, before there was even a book to do it, I was working and calling them up and telling them, you know what, we need a darkroom tool. I got to be able to dodge and burn. They didn’t have a dodge and burn. And I needed to, you know, do some colour shifting, and I need to get it right, you know. And if something is picking up too much colour from something else, and it needs to be adjusted so that it feels right, I need a tool for that. So over the years, in the beginning, I got my chops there, making it as close to the original as possible.

For further reading, check out our feature on 100 years of Leica:

Follow Joel Meyerowitz on Instagram @joel_meyerowitz and visit his official website at www.joelmeyerowitz.com. Joel Meyerowitz’s exhibition, “The Pleasure of Seeing” is currently on view at the Ernst Leitz Museum in Germany from June 29 to September 21, 2025.

Discover Leica cameras at leica-store.sg.

Credit for portrait photo: Maggie Barrett.