Remember that time on TikTok when we were all suddenly living Wes Anderson-inspired lives set to the soundtrack of The French Dispatch?

While not all of us may have jumped at the first chance to produce our version of the trend, a lot of us could understand this homage to the stylings of Wes Anderson, especially in his penchant for stunning aesthetics and specific colour palettes.

Perhaps this is why Paris, a city known for its own artistic expression, had decided to host Wes Anderson’s first-ever major retrospective that celebrates the film maker and his beloved cinematic universe.

As someone who still fondly remembers The Royal Tenenbaums as my first-ever Wes Anderson film, it took no convincing for me to make the trip 30 minutes away from the city centre to Cinémathèque Francaise just for the exhibition.

Located next to Parc de Bercy, Cinémathèque Francaise is known for its preservation of audiovisual heritage from the prehistory of cinema to that of present day, which makes it the perfect location to exhibit Wes Anderson’s his career retrospective.

I visited the exhibition on a weekday at around 1pm and though it was already was crowded during this time, I was still able to look at everything on display without having to muscle my way to the front.

The exhibition, like most cinematic themed ones, offers an overview of Wes Anderson’s career thus far chronologically, starting with his early projects Bottle Rocket and Rushmore, which starred a young Owen Wilson and Jason Schwartzman respectively.

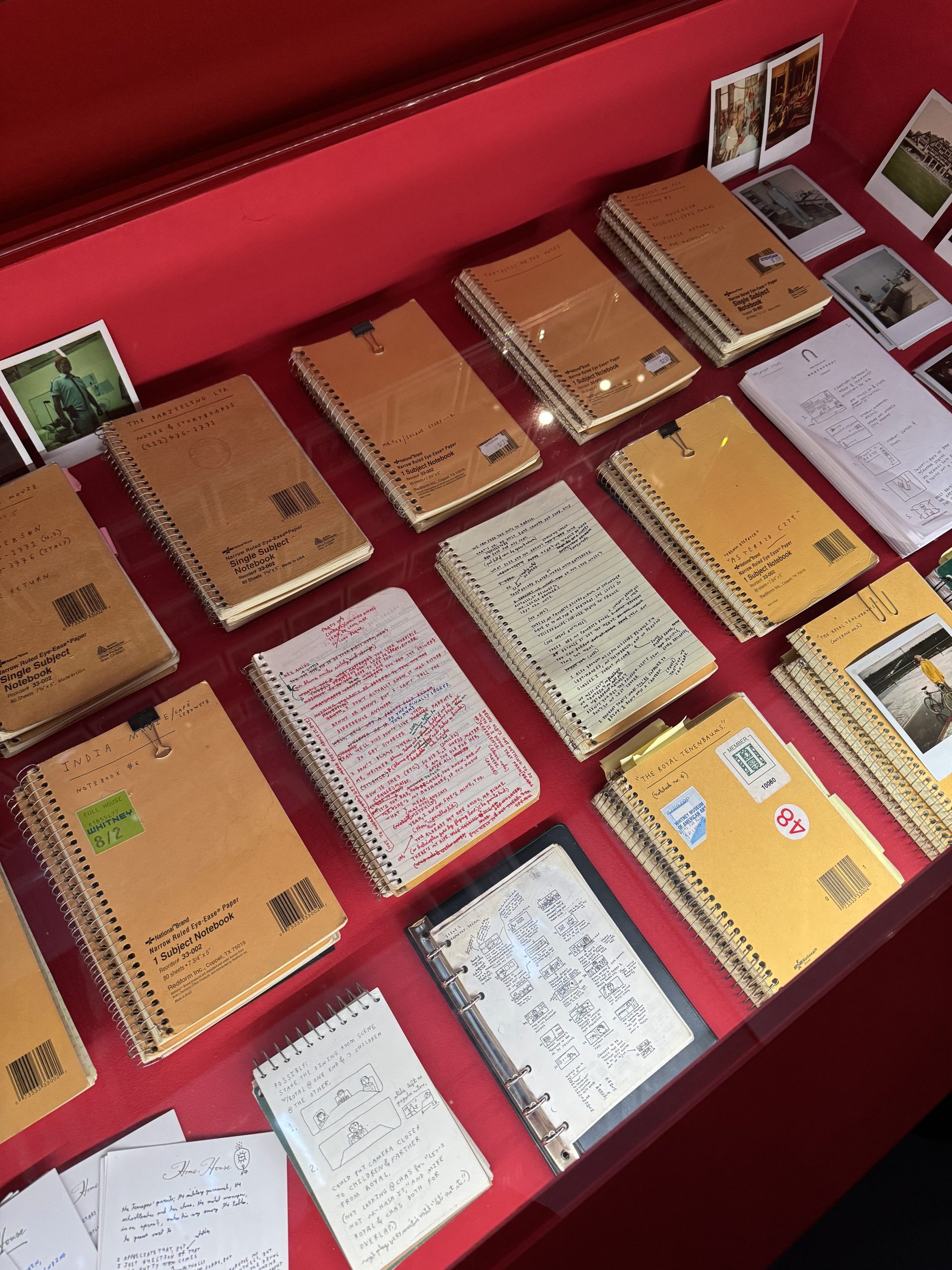

It was at this section where I was able to see Wes’ collection of notebooks that he kept of each film he worked on, which included The Darjeeling Limited, Fantastic Mr Fox, and the most recent Asteroid City.

Some of these notebooks were even opened, to give us exhibition-goers a peek at Wes’ process, from rough storyboard sketches to dialogues and the direction for the camera.

Similar to the Ghibli exhibition that has since concluded its run at the ArtScience Museum, this Wes Anderson Exhibition followed the same rule of thumb by carefully segmenting each space to fully celebrate every of his film, including his Oscar-winning short film adaptation of Roald Dahl’s The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar.

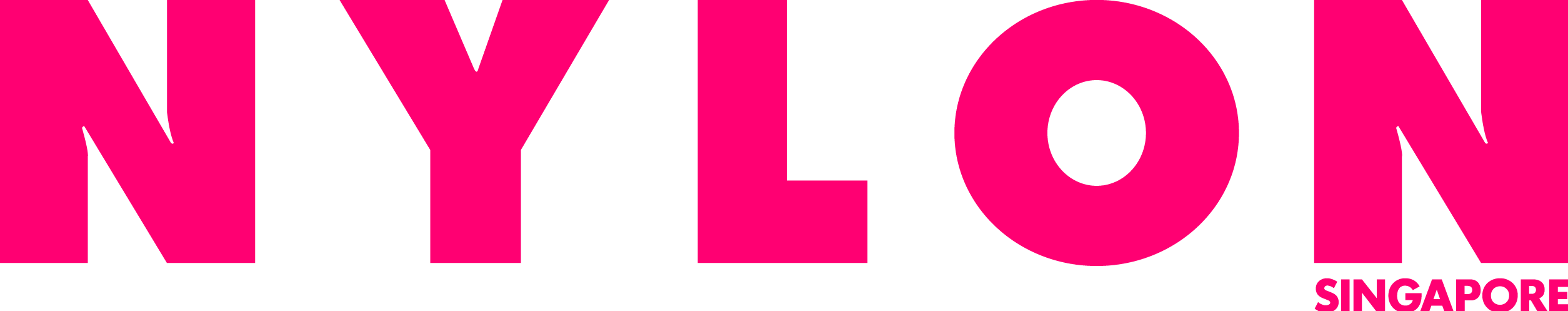

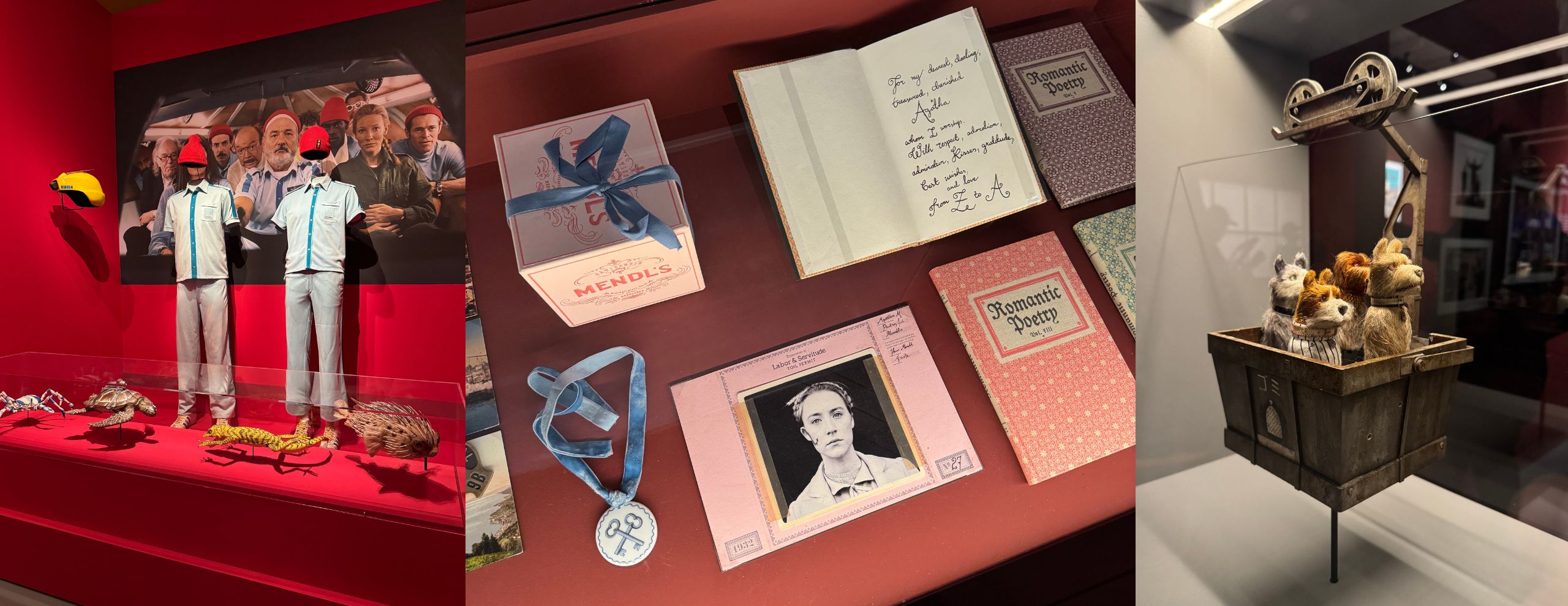

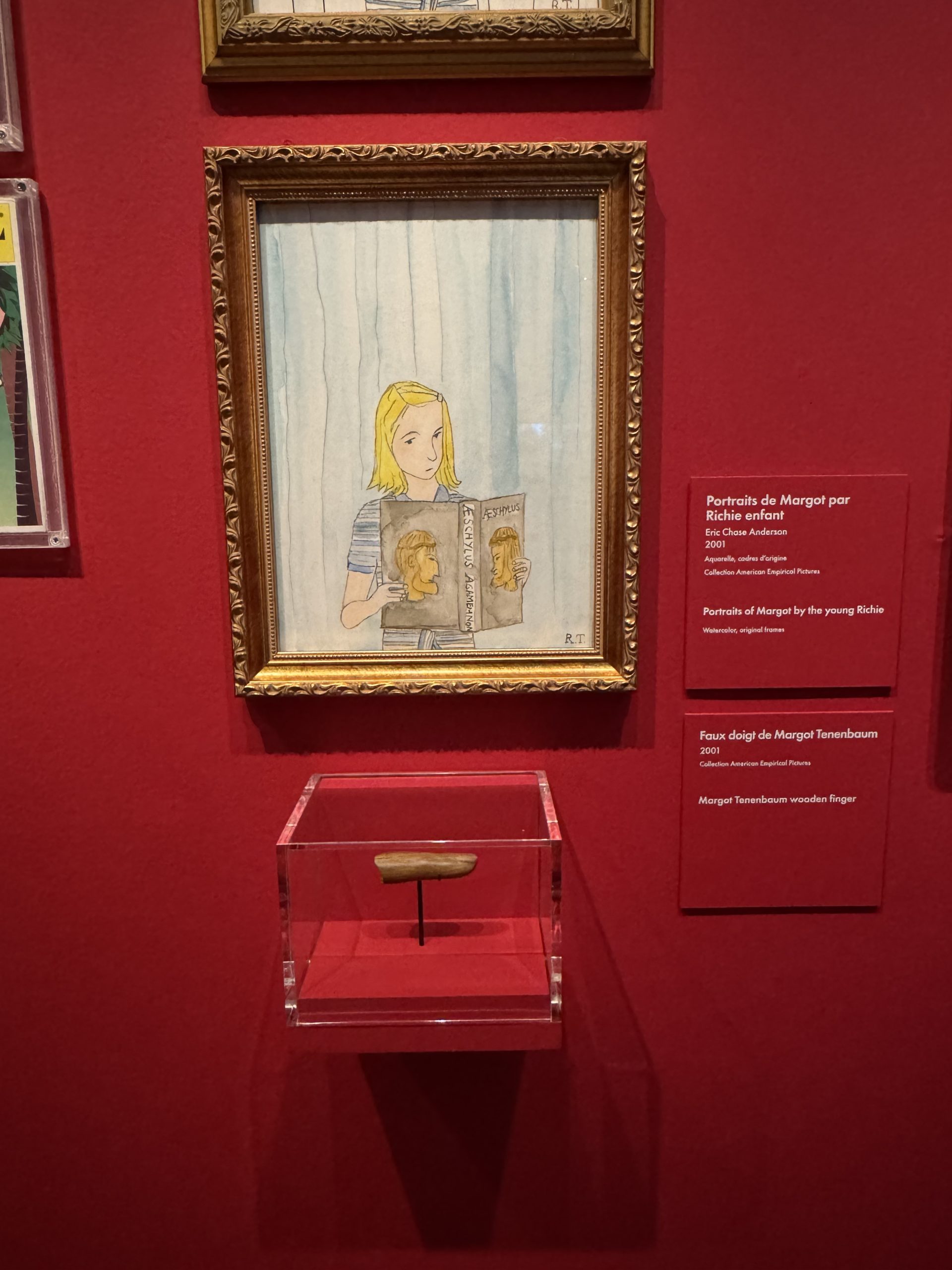

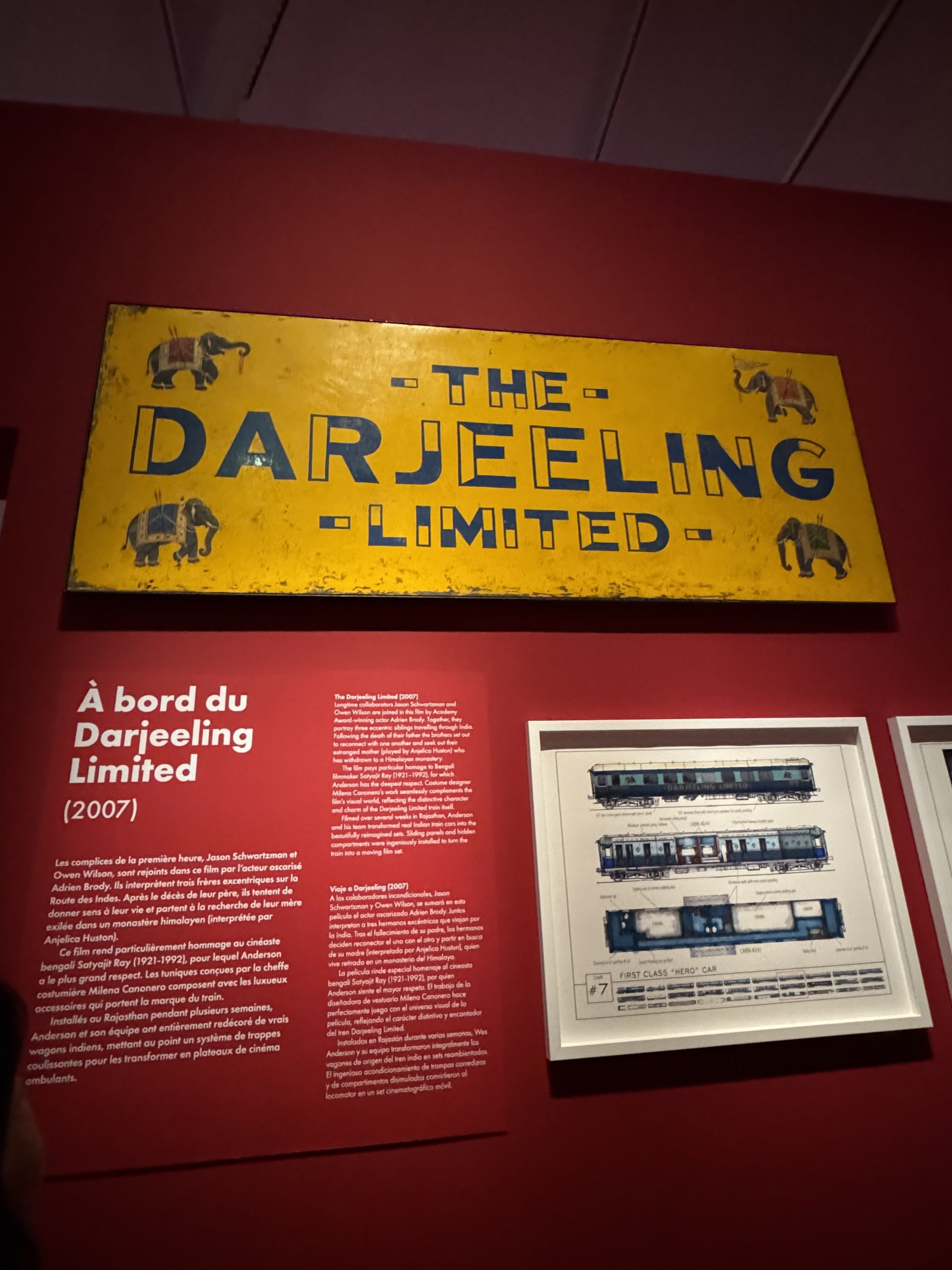

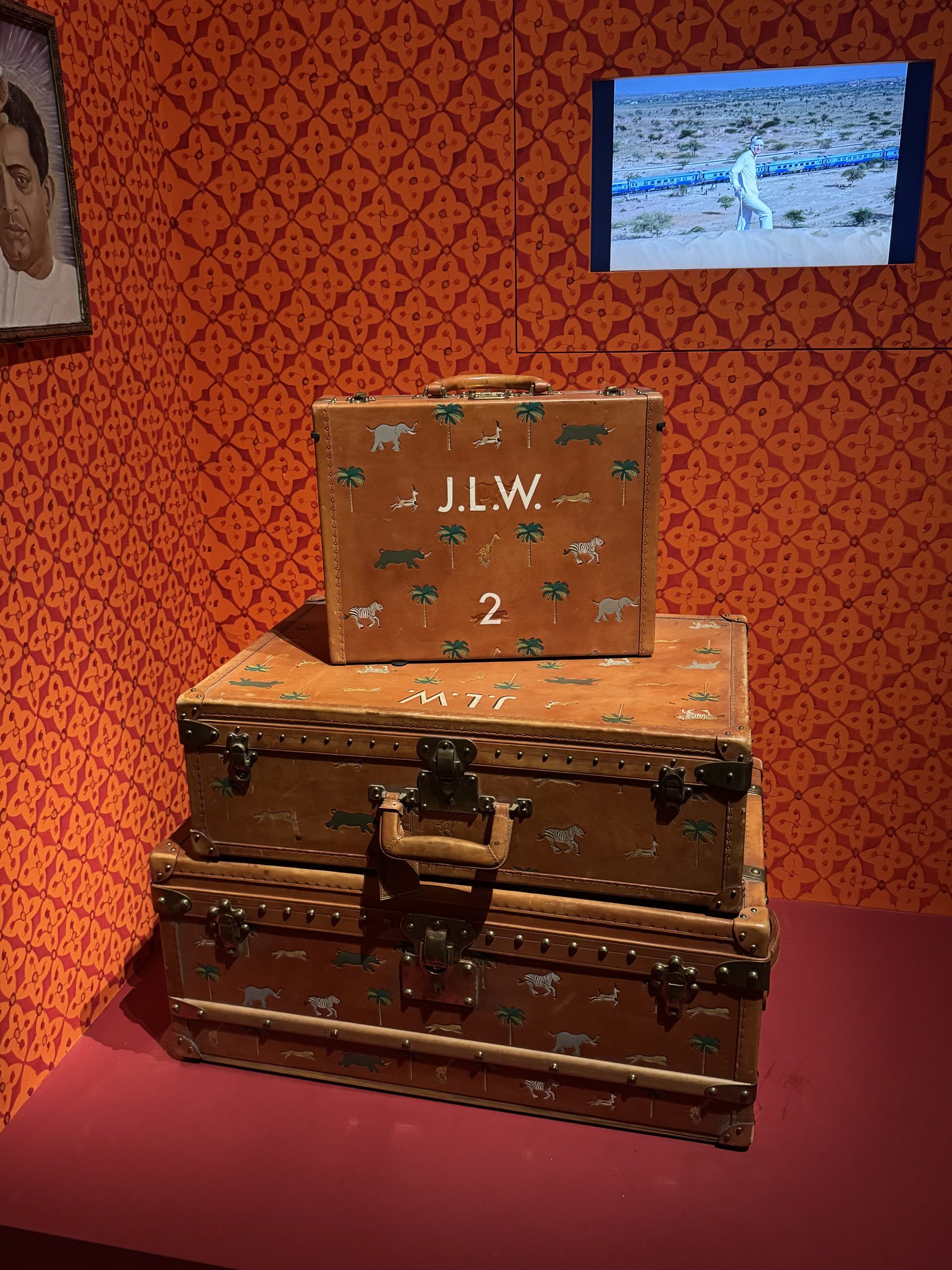

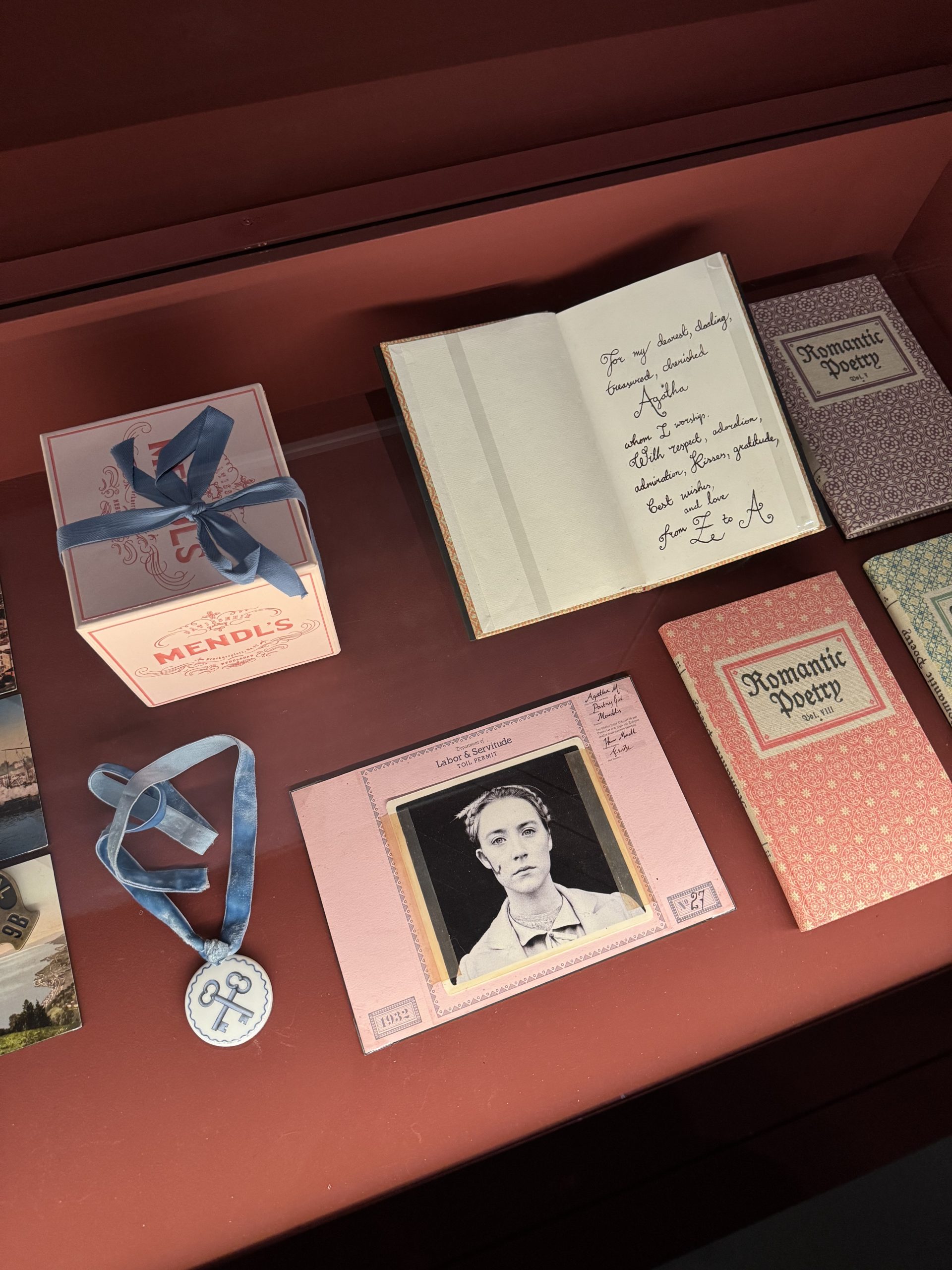

Costumes from The Royal Tenenbaums. Spot Margot’s wooden finger from The Royal Tenenbaums. Costumes from The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou. The signboard from The Darjeeling Limited. Suitcases that were designed by then-Creative-Director of Louis Vuitton Marc Jacobs, for The Darjeeling Limited. Costumes from Moonrise Kingdom. Costumes from The Grand Budapest Hotel. Can you find the iconic Mendl’s cake box? The crossing sign from Asteroid City.

Each of this space was decked with costumes and notes from the film, alongside iconic props you’ve seen on-screen, and a short video clip from each movie.

Having always loved the attention to detail that Wes Anderson had in his film, walking through this exhibition felt like a once-in-a-lifetime chance to get up close to these items that made his films so iconic.

I chuckled when I saw Margot’s wooden figure on display in The Royal Tenenbaums’ space, and couldn’t help but smile when I saw the models of the dogs from Wes’ stop-motion film, the Isle of Dogs.

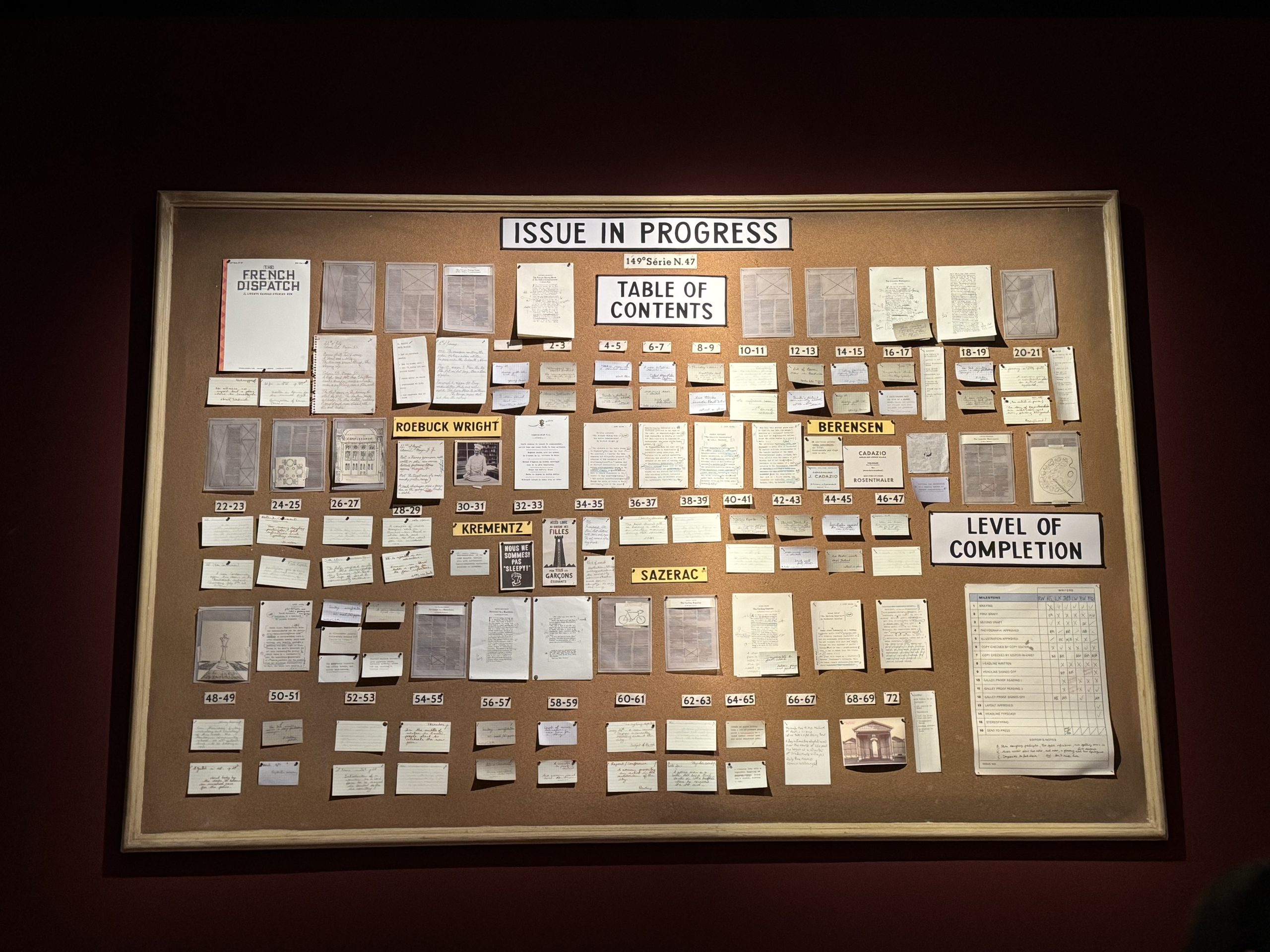

The delight I felt walking through the exhibition only increased when I came face to face with the gigantic ‘Issue-In-Progress’ board for The French Dispatch. I tried my hardest to read every piece of writing that was stuck to the board by zooming in with my iPhone, but it was an arduous task.

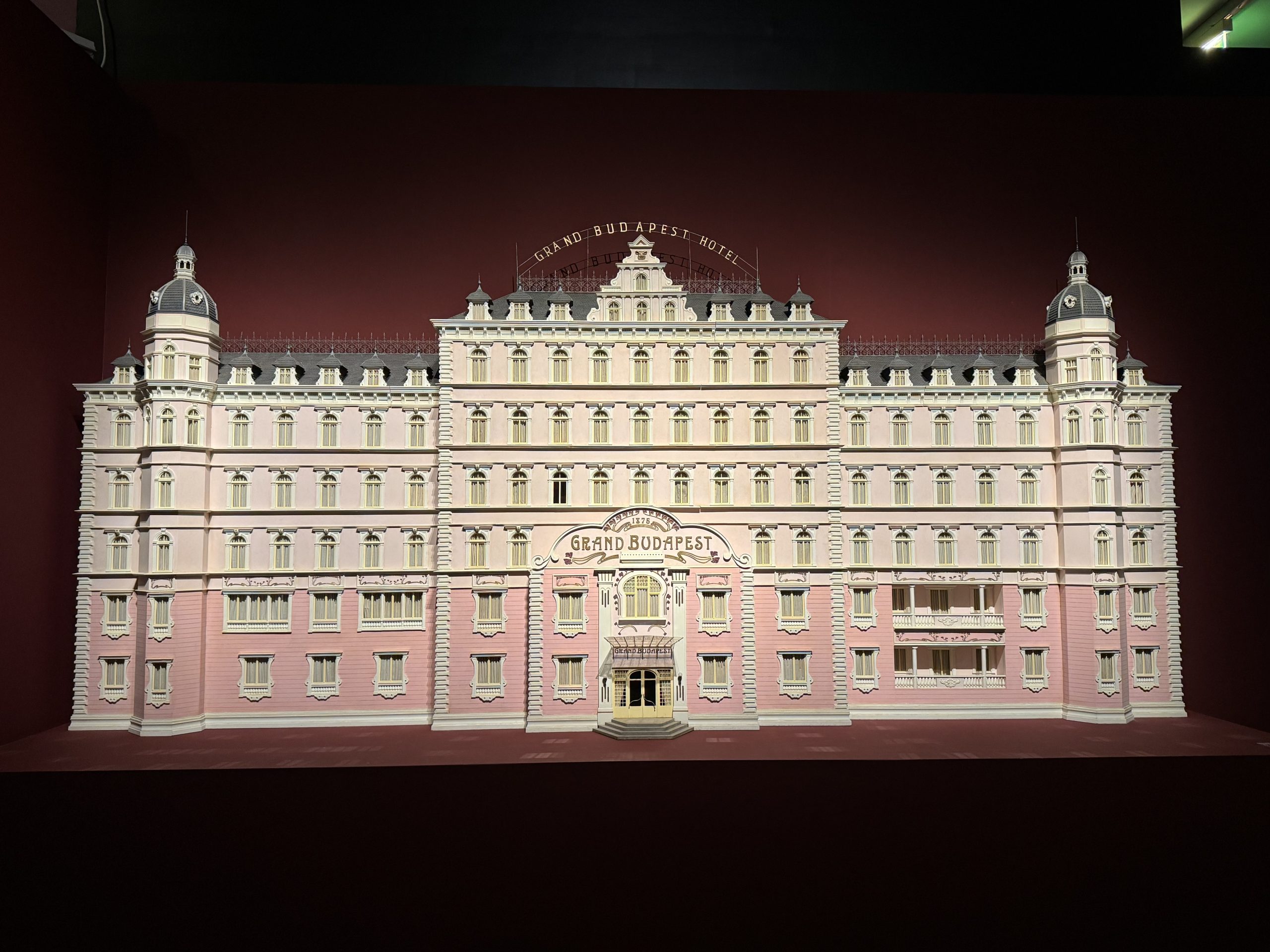

Though everything in the exhibition felt like a gem to me, nothing could beat the jaw-dropping moment I saw the miniature bubblegum and pale pink model of The Grand Budapest Hotel — which was the exact same model that Wes had used to film the exterior of the hotel that you see in the movie.

I’ve always appreciated Wes’ use of miniature props and sets as part of his film, because it gave the film a sense of authenticity that worked with his cinematic style.

Having the opportunity to look at some of these up-close really deepened my appreciation for Wes’ dedication to his craft for world building, and also reminded me that you don’t always need fancy CGI to tell a good story.